Fake hardware could open the door to malicious malware and critical failures.

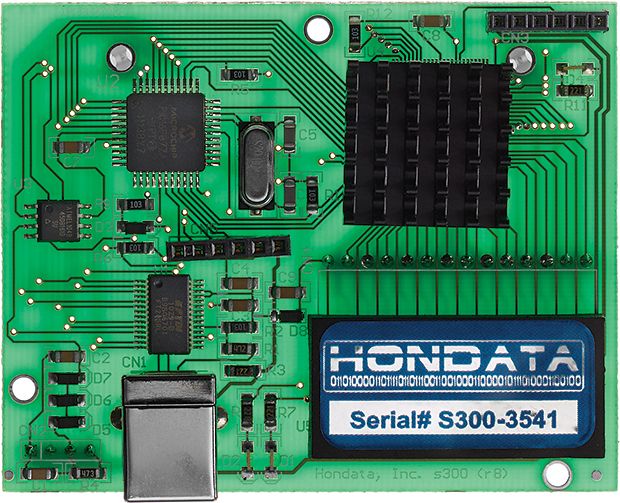

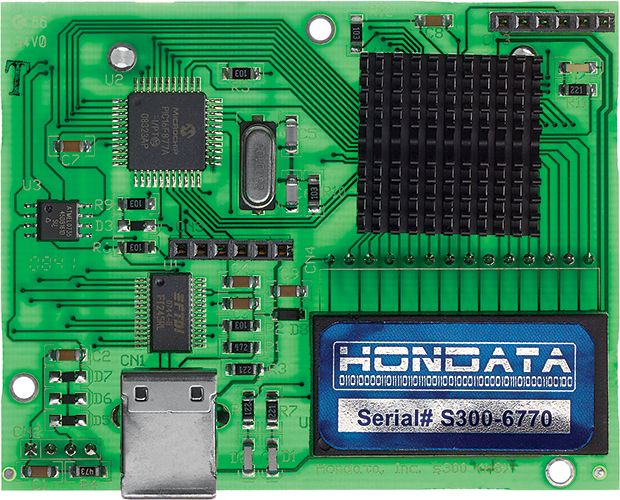

In February 2014, the FBI charged a Florida man, Marc Heera, with selling a cloned version of the Hondata s300, a plug-in module for the engine computer that reads data from sensors in Honda cars and automatically adjusts the air-fuel mixture, idle speed, and other factors to improve performance. The plug-in also allows users to monitor the engine via Bluetooth and make their own adjustments. The clones certainly looked like the genuine product, but in fact they contained circuit boards that had likely been built in China, according to designs Heera had obtained through reverse engineering. Honda warned that cars using the counterfeits exhibited a number of problems, including random limits on engine rpm and, occasionally, failure to start. Devices that connect to an engine control unit (ECU) present particular safety concerns; researchers have demonstrated that, through ECU access, they could hijack a car’s brakes and steering.

It’s not just car parts that are being cloned; network routers and parts for routers are also popular targets for cloners. That may not sound particularly scary until you consider that a hacker who has control of a cloned router can then intercept or redirect communications on the network. Look at the 2010 case of Saudi citizen Ehab Ashoor, who was convicted of purchasing cloned Cisco Systems gigabit interface converters with the intent to sell them to the U.S. Department of Defense. The devices were to be installed in Iraq in Marine Corps networks used for security systems and for transmitting troop movements and relaying intelligence from remote field operations to command centers.

While Ashoor appears to have been motivated by greed rather than any desire to do harm, the impact of ersatz equipment in critical electronic systems like a secure router or a car’s engine can still be catastrophic, regardless of the supplier’s intent.

And unlike counterfeit electronics of the past, modern clones are very sophisticated. Previously, counterfeiters would simply re-mark or repackage old or inferior components and then sell them as if they were new and top of the line; the main problem with these knockoffs was poor reliability. Cloned electronics these days are potentially more nefarious: The counterfeiters make their own components, boards, and systems from scratch and then package them into superficially similar products. The clones may be less reliable than the genuine product, having never undergone rigorous testing. But they may also host unwanted or even malicious software, firmware, or hardware—and the buyer may not know the difference, or even know what to look for.

|

|