The Reproducibility Revolution: How Computer Security Research is Grappling with Its Validity Crisis

In the world of computer security research, a quiet revolution is taking place. As the field grapples with concerns about a broader “reproducibility crisis” across all of science, researchers are not only questioning whether their experiments can be reproduced but fundamentally rethinking what validity means in computational research.

FICS Ph.D. student Daniel Olszewski has led two recent studies that illuminate the challenges and potential solutions facing the security research community as it attempts to build more reliable, verifiable science.

Beyond Simple Reproduction: The Tree of Validity

The first breakthrough comes from a comprehensive systematization that challenges how we think about reproducibility itself. After analyzing over 30 years of research on reproducibility and replicability, Olszewski and co-authors Tyler Tucker, CISE Interim Chair Patrick Traynor, Ph.D., and FICS Director Kevin Butler, Ph.D., developed the Tree of Validity (ToV) framework, a revolutionary approach that moves beyond the binary question of “Can this be reproduced?” to a more nuanced understanding of experimental validity.

“Reproducibility has been an increasingly important focus within the Security Community over the past decade,” Olszewski noted, “but reproducibility alone only addresses some of the challenges to establishing experimental validity in scientific research.”

Their research paper, published at the 2025 USENIX Security Symposium, develops a framework that explicitly demonstrates the different choices researchers can make when reproducing another’s work.

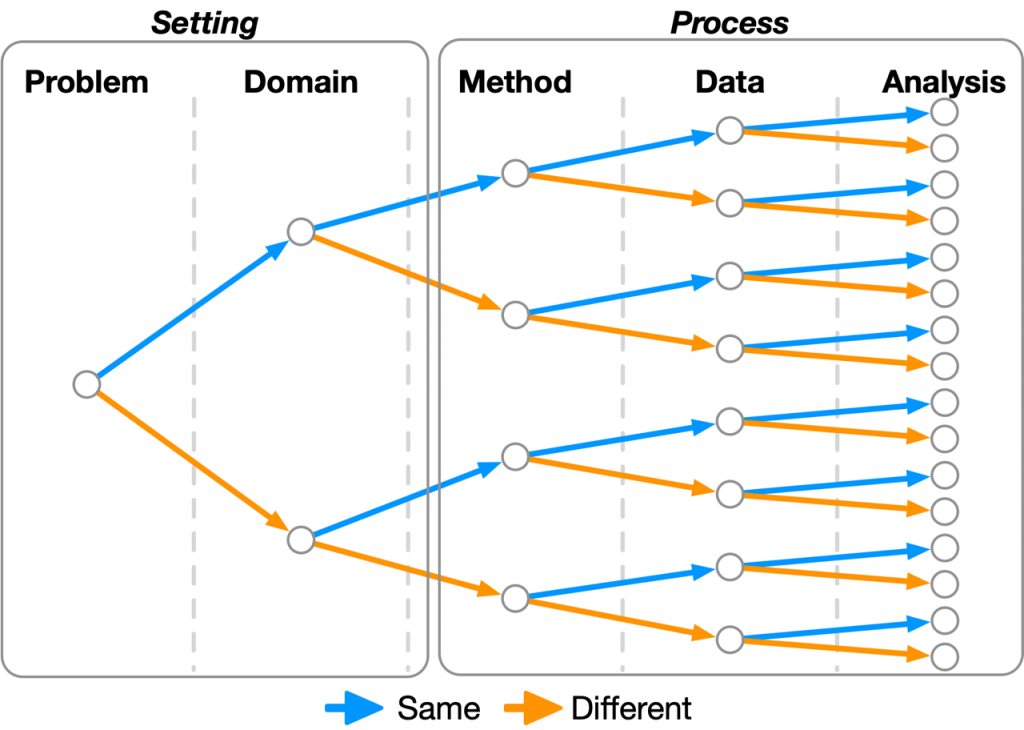

The Tree of Validity framework conceptualizes experiments as consisting of four key components: domain (or environment), method used, data collected and analysis techniques. Each component can either remain the same as the original study or be changed, creating a binary tree of all possible validity experiments. This allows researchers to precisely categorize and compare different types of validation studies, from exact reproduction to various forms of replication that test the limits and generalizability of findings.

What makes this framework particularly powerful is its recognition that reproducibility and replicability are not mutually exclusive or hierarchical.

“An experiment could be reproducible but not replicable, replicable but not reproducible, or both reproducible and replicable,” Traynor said. “With this framework, we now have a powerful tool to map contributions across multiple works and identify open questions.”

This nuanced view helps clarify longstanding confusion in the field about what different types of validation studies actually achieve.

The framework’s practical applications are already evident.

When applied to Distinguished Artifact Award winners from major security conferences, the Tree of Validity revealed that even papers with the highest reproducibility honors still face significant limitations. For instance, one award-winning study on GDPR cookie violations found that 14.9% of the original URLs no longer resolved when researchers attempted to reproduce the work, highlighting how time-dependent domains can make perfect reproduction (i.e., using the same code, data and experimental setup) impossible.

The Current State: Measuring Reproducibility in Practice

While the Tree of Validity provides a theoretical framework for understanding reproducibility, a parallel study examining Tier 2 applied security conferences reveals the current state of reproducible research practices in the field. This comprehensive analysis of over 2,000 papers from ACSAC, ACM AsiaCCS, IEEE Euro S&P and ACM WiSEC conferences spanning 2013-2023 examines how accessible and reproducible current security research actually is. Olszewski, Butler and Traynor, along with Sara Rampazzi, Ph.D., and other FICS researchers, published their findings in the 2025 ACM Conference on Reproducibility and Replicability, where they received a Best Paper Award.

The methodology for this evaluation was deliberately practical rather than theoretical. Researchers identified 579 papers that included links to code or data directly relevant to the authors’ findings, then attempted to reproduce results using objective criteria. They limited their debugging efforts to one hour per project (with extensions for machine learning training or complex C/C++ installations), reflecting the realistic time constraints faced by researchers attempting to build on others’ work.

The researchers assess whether the experiments are made available, the extent to which they run and if the results remain the same or similar.

“In this study, we were able to categorize the numerous challenges toward reproducible science and how existing theories fall short in practice,” Olszewski said.

Their requirement that results fall within 10% of claimed metrics provides a concrete threshold for successful reproduction, though this choice itself highlights ongoing debates about what constitutes successful validation.

Bridging Theory and Practice

Together, these studies reveal the complexity of validity in security research and the gap between aspirational frameworks and current practices. The Tree of Validity framework demonstrates that the field needs more sophisticated language for discussing different types of validation studies, while the Tier 2 conference analysis suggests that even basic reproducibility remains challenging to achieve in practice.

The implications extend far beyond academic exercises. Security research directly impacts the tools and systems that protect digital infrastructure, making the reliability and verifiability of findings critically important. When a security paper claims to detect vulnerabilities or propose defensive measures, the ability to independently verify and extend those findings can have real-world consequences for cybersecurity.

The Tree of Validity framework offers a path forward by providing pathway for expressing experimental methodologies more precisely. Rather than simply labeling studies as reproducible or not, researchers can specify exactly which components of their experiments can be independently verified and which require different approaches.

The Road Ahead

As the computer-security field continues to mature, these studies suggest that progress requires both better theoretical frameworks for understanding validity and more practical efforts to make research artifacts accessible. The introduction of Artifact Evaluation Committees at major conferences represents important progress, but the Tree of Validity framework suggests the community should expand beyond simple reproducibility to embrace various forms of replication that test the robustness and generalizability of findings.

The ultimate goal is not perfect reproduction, which may often be impossible, but rather building evidence toward or against scientific hypotheses through multiple independent studies.

“A more systematic approach to replicability and reproducibility can lead to a new understanding within and beyond computer security,” Butler noted.

In a field where security threats constantly evolve and experimental conditions change rapidly, this broader view of validity may be not just useful but essential.

The reproducibility revolution in computer security research is just beginning, but these studies provide both the theoretical foundation and practical roadmap for building a more reliable, verifiable science that can better serve our increasingly digital world.